Learning about COVID-19 in Nepal

Learning Brief

28/05/2020

________________________________________________________________________________

When I look back at the chronology of my Facebook page regarding COVID-19, I see that I had first come to know about it in late January earlier this year. I had shared a report published by The Guardian that raised the issues of the possibility of the COVID becoming an epidemic and whether the world should panic or not.

Following it, after almost 3 months of the detection of COVID in Wuhan in China in December 2019, the World Health Organisation (WHO) announced the Corona Virus Disease-2019 (COVID-19) as an epidemic on 11 March 2020. What took WHO almost a quarter of a year to

declare COVID as an epidemic is beyond the scope of this learning brief.

Back home in Nepal, the first case of COVID-19 pandemic was confirmed on 23 January 2020 when a 31-year-old male student who had returned to Kathmandu from Wuhan on 9 January, tested positive for the disease. The Ministry of Health and Population (MoPH), Government of Nepal, started taking note of COVID-19 since late January and the country’s first COVID situation report was published on 28 January. Since then the situation reports have been published by the ministry every day on its website and summarised updates disseminated through various mass media such as TV, radio and social media.

Eventually, almost two months after the detection of the first COVID case in Nepal, to contain the spread of the virus nationwide lockdown was imposed by the government from 24 March 2020. The latest situation report number 108 published on 27/05/2020 indicates that the total positive COVID cases in Nepal has reached 886 and 4 fatalities. The data on positive cases has been reported by the ministry disaggregated gender, age, province and district wise.

In a column authored by Dr. Buddha Basnet published by the Nepali Times on 19 March 2020 it says, “The Wuhan data from Chinese doctors revealed that it was the elderly (mostly male) that took the brunt of the disease and that children were not symptomatic, even though they may be infected by the virus. The findings also showed that about 1% of the patients who suffer from COVID-19 die.” It further added, “The Wuhan data from Chinese doctors also revealed that it was the elderly (mostly male) that took the brunt of the disease and that children were not symptomatic, even though they may be infected by the virus.”

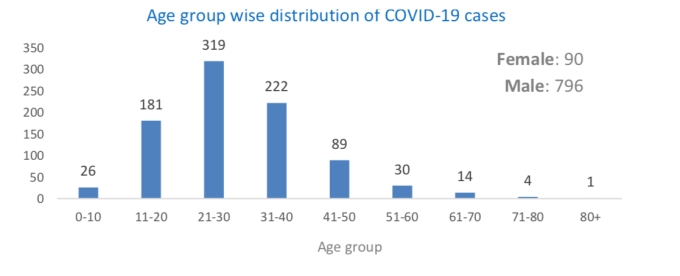

In contrast to the findings from the Wuhan data, when we look at the latest COVID data from the situation report published by the ministry, we find that of the total 886 positive cases to-date in Nepal the highest number of 319 (36%) has been between 21-30 years’ age group, followed by 222 (25%) between 31-40 years’ age group. Unlike the Wuhan data in Nepal only 19 (2%) positive cases have been of elderly or above 60 years’ age group. However, as the Wuhan COVID study had projected, in the case of Nepal also with the latest data of 886 and fatality number of 4, the death rate of 0.5% hovers around almost 1%.

Source: COVID-19 Situation Report, 27 May 2020, MoPH

Source: COVID-19 Situation Report, 27 May 2020, MoPH

According to the same Dr. Basnet’s column, the incubation period (the time from infection to symptoms) was also studied in Wuhan and formed the basis of the quarantine period of 14 days. The average incubation period is five days but may be up to 12 days. To be on the safe side a two-week quarantine was recommended, after which it is unlikely that the symptoms will manifest. In Nepal there have been however cases which has taken more than 14 days to manifest. As in the case of all the three members of a family residing in Sun City Apartments in Teku, only 28 days after they returned to Kathmandu from United Kingdom they were tested positive in random diagnostic test.

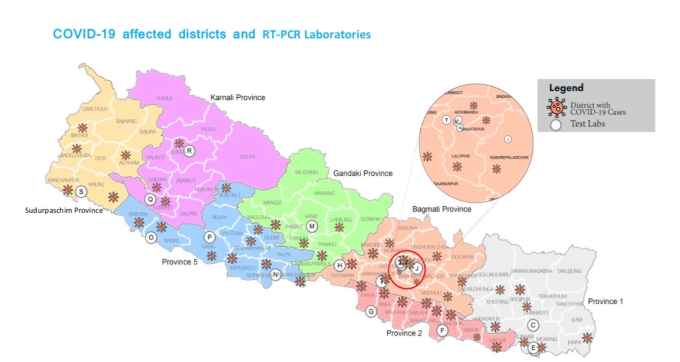

Another interesting learning from the COVID data so far in Nepal has been that the 47 districts with COVID positive cases are primarily from the tarai flatlands. The high hills and the mountain districts seem to be untouched by COVID so far. However, it is yet to be scientifically ascertained that prevalence of COVID cases in the tarai flatlands of Nepal are due to ecological reasons or the reversal of Nepali migrant population from India.

Source: COVID-19 Situation Report, 27 May 2020, MoPH

Source: COVID-19 Situation Report, 27 May 2020, MoPH

As far as learning about the economic impact of COVID-19 in Nepal is concerned, the World Trade Organisation in a brief issued recently states, “Nepal is starting to suffer the most abrupt and widespread cessation of economic activity due to outbreak of this virus. As per the analysis by the Asian Development Bank, the outbreak of this deadly disease will hit almost every sector of the Nepali economy, shaving up to 0.13 per cent off the gross domestic product and rendering up to 15,880 people jobless.” It further adds, “The impact has already started to surface in number of sectors like tourism, trade and production linkages, supply and health. Especially the entire service industries: tourism, aviation and hospitality sector have been hit hardly by the outbreak.”

From the pattern of cases that is surging in Nepal everyday it is obvious that the most vulnerable infection and socio-economic wise has been the returnee migrant workers primarily from India and their families. And as the reversed migrant workers coming back to Nepal, especially from India has been in thousands, the actual number of unemployed due to COPVID-19 have definitely surpassed by several folds the number estimated by Asian Development Bank. It is also apparent from the very onset of the COVID-19 response from the government by imposing the lockdown that the most effected has been the daily wage workers in the non-agricultural informal service sectors. Though the actual number or data on COVID effected daily wage workers or in service sectors is not available, adding three main employment sectors of service, returnee migrant workers and the daily wage workers in Nepal the number of unemployed would definitely cross the Bank’s estimate. It is also to be noted that the main contributor to total employment in Nepal is the informal non-agriculture sector, accounting for 41 percent of all jobs.

The learning we have so far from the data and information available has been all very useful for the government as well as the civil society and others to respond to the pandemic. However, what we need to learn more from tangible and reliable data and information is which social and economic sections of the society have been the most vulnerable and have been subject to marginalisation due to the pandemic.

A recent research report in America on the impact of COVID race and ethnicity wise as of 19 May, with the pandemic claiming about 99, 000 deaths, data about the race and ethnicity of the deceased known for 89% of these deaths, compiled from Washington, D.C. and other 40 states from which data were obtained, states that, “While the result of the research was an incomplete picture of the toll of COVID-19, the existing data revealed deep inequities by race, most dramatically for Black Americans. The latest overall COVID-19 mortality rate for Black Americans was 2.4 times as high as the rate for Whites and 2.2 times as high as the rate for Asians and Latinos. Aggregated deaths from COVID-19 in these 40 states and the District of Columbia had reached new highs for all groups as: 1 in 1,850 Black Americans has died (or 54.6 deaths per 100,000); 1 in 4,000 Latino Americans has died (or 24.9 deaths per 100,000); 1 in 4,200 Asian Americans has died (or 24.3 deaths per 100,000); and 1 in 4,400 White Americans has died (or 22.7 deaths per 100,000).”

This much we can say we have been able to learn so far about the technical and socio-economic dimensions of COVID-19 prevalence in Nepal. For more accurate learning that could assist in more accurate social and economic interventions or responses by the government as well as the civil society, the current disaggregated data gender and age wise managed by the MoPH, in cooperation with other sectoral ministries and development partners needs to be further disaggregated social and economic wise.

________________________________________________________________________________

Prepared and published by Kishor Pradhan, Independent Development Consultant/CEO, Development Knowledge Management and Innovation Services Pvt. Ltd, Lalitpur, Nepal

kishorpradhanktm@gmail.com; 977-9851040564; 27 May 2020, 2:30 pm (NST)

Written by Rem Bahadur BK

Written by Rem Bahadur BK